Babies expect fairness, and prefer people who behave with fairness

© 2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

opens IMAGE file

opens IMAGE file

Babies expect adults to share resources equally. They prefer people who deport with fairness. Simply babies are also learning well-nigh selfishness and favoritism. Can we go the role models our children deserve?

Everyone should get a fair share.

It's the organizing principle of hunter-gatherer societies, and a familiar concept worldwide.

Even in cultures that promote hierarchy, people tend to resent gross inequality.

In experimental games, people around the world impose penalties on players who attempt to split up upwardly prizes in a skewed, discriminatory way (Ensminger and Henrich 2014; Henrich et al 2006).

But when does information technology get-go? How early in life do we brainstorm to notice inequality? To expect fairness? To care about the way resource are divided upward?

You might guess that information technology happens during the preschool years. That period between 3 and 5 years, when children are highly mobile, talkative, and ready to fight for their interests.

Such children have many opportunities to witness the segmentation of resources they care nearly, like treats and toys. They take the verbal skills to negotiate. So peradventure this is when kids start learning nearly the off-white allocation of appurtenances.

It sounds plausible, but it'south wrong.

Equally information technology turns out, babies know quite a bit about fairness.

They seem to look that adults volition distribute resources equally.

They seem to anticipate that acts of unfairness will provoke our condemnation.

And — given the choice — babies evidence a preference fair-minded individuals. They volition selectively arroyo adults who they've seen treat others with fairness.

How practice nosotros know? What factors influence our children? And what tin can we do to nurture a sense of fairness? Hither are the details.

Experimental research: Babies expect adults to dissever up resource in a fair, equal style

The offset testify came from experiments on older infants living in the U.s.a..

Marco Schmidt and Jessica Sommerville showed 37 babies (aged 15 months) several mini-movies — video clips depicting a pair of women sitting at a dining tabular array.

Each video prune began the same way.

- The diners wait.

- A third person (let's call her the "Benefactor") arrives with food.

- The diners eye the food and make enthusiastic comments. "Yummy!"

Simply what happened next varied from i clip to the adjacent.

- In some video clips, the Benefactor gave each diner the same amount of food (e.m., each woman received two graham crackers).

- In other video clips, the Distributor divided the food unequally (e.g., one woman received a single graham cracker, while another received three).

So. Two different endings — one fair, one unfair. How did the babies feel about it?

The researchers couldn't interview the babies to find out. These infants hadn't yet developed the necessary linguistic communication skills.

But there is some other fashion to gain insight into a babe's heed.

Scientists take long established that babies tend to look longer at events that surprise them. Thus, if y'all measure looking times, and compare them, yous can get a feeling for what babies await.

A long stare suggests that something has violated the infant's expectations.

What happened in the case of the graham cracker vignettes?

Babies acted as if they were surprised by the unequal distribution of food. They stared longer at the unfair consequence.

And the babies' surprise wasn't focused on the nutrient per se. It was the human being element that mattered.

We know this because the researchers ran a control condition featuring video clips without human actors. Some video clips showed a tabular array with equal amounts of food. Others showed nutrient distributed unequally:

When shown these video clips, the babies spent the same amount of fourth dimension looking — regardless of the outcome (Schmidt and Sommerville 2011).

So the babies' expectations were focused on people. Somehow, by the age of 15 months, these babies had learned a cultural norm of fairness. When people distribute nutrient, they are supposed to give every recipient an equal portion.

Subsequent studies have replicated the effect, and documented expectations of fairness in fifty-fifty younger babies (Sommerville and Enright 2018).

For example, a lab in Italia has reported expectations of fairness in x-month-former babies (Meristo et al 2015).

Another research group — in the The states — plant bear witness for expectations of fairness in both ix-month-old and iv-month-sometime infants (Buyukozer Dawkins et al 2019).

It seems, and so, that we're on pretty solid ground if nosotros assume that babies — past the beginning of their first twelvemonth — sympathize something near equitable sharing.

But does that tell usa that babies think fairness is practiced?

Are babies little egalitarians? Practise they actually endorse the equal distribution of resources?

That's difficult to say. Maybe babies don't take whatever moral intuitions or preferences about it. They simply have a sense for what'southward normal. They've learned that people unremarkably dissever things up in an equitable way.

But in that location is intriguing evidence to the contrary.

Study: Babies act as if egalitarian sharing is a distinguishing characteristic of the "good guys"

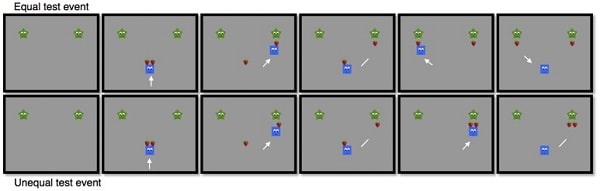

Surian and colleagues (2018) tested the thought by presenting animated video clips to a group of 14-month-old babies in Japan.

The researchers began by introducing the infants to a couple of cartoon characters:

- One character was prosocial. The babies watched every bit this character offered assist to someone trying to climb upward a hill.

- The other grapheme was antagonistic. It actively thwarted the hiker's efforts.

Then, the babies watched a new set of video clips. Each prune featured one of the previously-encountered characters, but now the characters were acting as Distributors — allocating red berries to a pair of would-be recipients.

As in the alive-action "graham cracker" experiments, events varied from i video clip to the next.

- In some clips, babies witnessed the Distributor behaving fairly. Each recipient received a berry.

- In other clips, babies saw the Distributor deed unfairly. One individual received two berries. The other got nix.

And once again, the researchers tested the effects of off-white and unfair distribution scenarios on a baby'due south looking time. The effect?

Babies withal had expectations regarding fairness, only they seemed to modify their expectations based on a graphic symbol's prior behavior.

When babies saw the previously helpful character being unfair, they acted surprised. They stared longer.

Babies also acted surprised when the observed the previously antagonistic character acting fairly.

It's a effect that suggests babies practice more await fairness. They expect fairness from a specific type of individual — someone who is helpful or kind. Fairness is a distinguishing feature of "the good guys."

And this interpretation gets support from another study — a study testing babies' expectations about praise and censure.

Study: Babies anticipate that nosotros'll condemn acts of unfairness

Researchers began by replicating the "graham cracker" procedure used by Schmidt and Sommerville: They presented 15-month-old babies with video clips of a Demonstrator handing out food to a couple of women (Deschamps et al 2016).

But this fourth dimension, researchers added a new footstep. Immediately after each video prune ended, the presented babies with a close-up of the Distributor's face.

The face didn't move or speak. The Distributor remained withal and tranquillity. And while the babies watched this face, there was a vocalism-over. A stranger's voice — filled with emotion — was making comments about the Distributor.

The nature of the comments varied.

- After some clips, the voice enthusiastically praised the Distributor. Babies heard the phonation say things like: "She's a good daughter. She did a skilful job!"

- Later other clips, the vox admonished the Distributor, maxim things like: "She's a bad girl. She did a bad task!"

How did babies react? It depended on what they had witnessed in the preceding video clip.

For example, if they had simply seen the Benefactor dividing up resource unfairly, the babies seem to await disapproval. They didn't await very long when the vocalism admonished the Distributor.

Only if the voice praised the unfair Distributor, the babies stared.

Babies as well show an interesting developmental blueprint: Individuals who wait fairness are more likely to appoint in generous acts of sharing.

For evidence, let'due south get back to the original experiments by Schmidt and Sommerville.

We saw that the babies acted surprised when the Distributor behaved unfairly. Merely that was the outcome for babies on average.

Not every baby followed the trend. Some babies didn't human activity surprised by the unequal distribution of nutrient.

So Schmidt and Sommerville wondered. Does a infant'southward personal expectations have whatsoever bearing on the mode he or she treats other people? Are expectations of fairness linked with personal acts of generosity?

To find out, the researchers conducted a follow-up test. It went like this.

- Each baby sat on his or her mothers' lap. The baby was offered two toys.

- The researchers noted the baby's favorite, and and so asked the infant to hold both toys (1 in each hand).

- Next, a stranger arrived and asked for a toy. ("Tin I take one?")

3 outcomes were possible.

- A baby could hand the stranger the preferred toy.

- A baby could manus the stranger the non-preferred toy.

- Or a babe could fail to respond altogether.

What happened?

Virtually babies handed over a toy, but in that location was an interesting difference in the level of generosity shown.

Among babies who shared, those who had expected fairness in the previous experiment were very likely to share their preferred toy.

Past contrast, babies who didn't look fairness were less altruistic. The vast majority (12 out of 13) handed over their not-preferred toy.

As the authors argue, this suggests that sharing and fairness expectations are developmentally linked. Noticing fairness — viewing it as normal — was continued with a babe'southward willingness to share highly-valued objects.

Finally, in that location's show that babies actively prefer individuals who distribute resources in a off-white, equitable way.

In an experiment on 13- and 17-month-sometime infants, Kelsey Lucca and colleagues (2018) repeated the graham cracker procedure.

Once once again, babies watched video clips of human being actors sitting at a dining table. And once more, the endings varied.

- One clip featured a woman giving two diners an equal number of crackers to eat.

- Another clip showed a different woman distributing grossly unequal portions.

Each baby viewed both clips, and, immediately after, the baby was presented with an opportunity.

The baby was in a room with two, large monitors. Every bit you can run across from the photo, each monitor featured a different Benefactor, and each Distributor appeared to exist gazing at the viewer…and offer a toy.

Just beneath each monitor was a kind of delivery apparatus — a xanthous tube emptying into a container.

The researchers designed this set-upward to create the illusion that the on-screen women could ship their toys through the tubes and into the containers below. And that'south just what each woman appeared to do.

Babies watched these actions, which occurred simultaneously. And so they were given a selection. They could arroyo one of the women and retrieve a toy.

Just which woman would they approach? The fair Benefactor? Or the unfair Distributor?

The babies voted with their feet, and most showed the aforementioned preference. Virtually 80% (24 out of 30) went for the woman who had acted adequately.

How do babies develop these notions? Everyday interactions — including those with siblings — play a part.

The behavior nosotros find in these experiments seems spontaneous. Babies weren't deliberately trained to expect equal portions. Nobody instructed told them to expect fairness from the "adept guys." Nobody taught them to prefer people who follow egalitarian principles.

And, as I mentioned in the introduction, hunter-gatherers — the peoples whose life-ways well-nigh closely match those of our ancestors — are intensely egalitarian.

Hunter-gatherers don't tolerate individuals who endeavour to "become higher up themselves." Such people are ridiculed, sanctioned, and ostracized.

So at that place's a case to be made that egalitarian ideas are cardinal to the human playbook. An attribute of human nature.

Merely that doesn't mean it just happens.

A crucial point about "human nature" is that we learn. If nosotros tend to develop along sure lines, information technology usually isn't because we're "hardwired" to turn out the aforementioned mode, regardless of environmental inputs. Our experiences shape us.

This is undoubtedly true of attitudes and preferences most egalitarianism and fairness. The prove indicates that baby's experiences are important.

For case, if fairness is something we learn, then we ought to see a correlation with learning opportunities: Babies should develop expectations of fairness earlier if they are exposed to more frequent examples of people dividing up resources.

And this prediction is consistent with a written report by Talee Ziv and Jessica Sommerville.

The researchers tracked 150 babies for nine months, and constitute that the development of fairness expectations had little to do with the country of a child's motor skills or language ability.

Instead, a primal predictor was having siblings (Ziv and Sommerville 2016). Kids adult fairness expectations before in life when there was somebody at dwelling to share with.

And let'south confront another reality. Babies don't ever presume that we'll distribute resources equally. At some indicate forth the mode, they learn nearly corrupt ability-grabs and favoritism.

We saw hints of that in the animated "good guy, bad guy experiment." Babies didn't expect the antagonistic character to distribute resources fairly.

But in that experiment, babies didn't know annihilation almost the potential recipients. They had no reason to predict which individuals the unfair Benefactor would favor.

What if we provide this information? Do babies expect that certain types of individuals will get more than their off-white share? That say-so figures will prop upwards aggressors or elites?

These are precisely the findings of Elizabeth Enright and her colleagues (2017).

The researchers performed their experiments using 2 puppets, and they began by confirming that 17-month-erstwhile babies will respond to puppets just equally they practice to human beings:

When a man distributed unequal portions to these puppets, and the babies acted surprised.

But that'due south when babies don't have any background information about the ii puppet characters.

And so the researchers ran another experiment, one that included a prologue.

Babies watched the puppets collaborate with each other, and noticed that one was boob was stronger, bossier, more ascendant.

For instance, when the two puppets competed to sit on a fancy chair, one came out the articulate winner. He got his manner.

After seeing this power struggle, the babies were randomly assigned to watch different distribution scenarios.

- Some saw a human experimenter dole out equal portions to the puppets.

- Others witnessed the experimenter giving out diff portions.

And the results?

When the Distributor gave more than to the dominant puppet, the babies took this in their stride.

Information technology was the fair issue — an equitable distribution of prizes — that made babies do the double-take (Enright et al 2017).

So what's the practical takeaway?

We've got one more reason to care for our infants as thinking, feeling, socially perceptive beings.

Babies are doing much more than opens in a new windowlearning to clamber, opens in a new windowwalk, and opens in a new windowtalk.

From an an early historic period, they are watching united states. Watching and figuring things out, and not only when we're direct engaging them in chat.

Every bit important as direct engagement is for a baby's development, it'southward just one piece of the puzzle.

Babies also pay attention to — and learn from — the social interactions of other people.

They absorb information about the relationships of third parties.

They learn about social norms, power plays, and morality.

So if you've heard of babies characterized as "piffling psychologists" (learning well-nigh other people'southward thoughts and feelings), and "little physicists" (learning well-nigh gravity and physical properties of objects), hither's some other job title to the list: Our babies are also "little anthropologists."

They aren't but studying our fine words and ideals. They are studying our actual behavior, warts and all. And we couldn't cease them, even if we wanted to. They acquire from our case.

So let'south strive to evidence them our best.

More reading

Tin we teach empathy and compassion? Tin can nosotros help our children develop better social skills? See my evidence-based tips for nurturing empathy, and these Parenting Scientific discipline social skills activities.

And for more fascinating information nearly your baby's developing mind, check out these Parenting Science manufactures:

- opens in a new windowNewborn cognitive development: What are babies thinking and learning?

- opens in a new windowDo babies feel empathy?

- opens in a new windowMoral sense: Babies prefer underdogs and practice-gooders

- opens in a new windowTalking to babies: How friendly middle contact helps infants "melody in"

- opens in a new windowTin babies sense stress in other people?

- opens in a new windowWhen practice babies speak their kickoff words?

References: Babies expect fairness

Burns MP and Sommerville JA. 2014. "I pick you": the touch of fairness and race on infants' selection of social partners. Front Psychol. 2022 Feb 12;5:93.

Buyukozer Dawkins Yard, Sloane S, Baillargeon R. 2019. Practise Infants in the First Twelvemonth of Life Expect Equal Resources Allocations? Front Psychol. x:116.

DesChamps TD, Eason AE, Sommerville JA. 2015. Infants Associate Praise and Admonishment with Fair and Unfair Individuals. Infancy. 21(four):478-504.

Enright EA, Gweon H, Sommerville JA. 2017. 'To the victor go the spoils': Infants wait resource to align with dominance structures. Noesis. 164:8-21.

Ensminger J and Henrich J (eds). 2014. Experimenting with Social Norms: Fairness and Punishment in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Russel Sage Foundation.

Hamlin JK and Wynn K. 2011. Young infants prefer prosocial to hating others. Cogn Dev. 26(1):30-39.

Henrich J, McElreath R, Barr A, Ensminger J, Barrett C, Bolyanatz A, Cardenas JC, Gurven M, Gwako Due east, Henrich N, Lesorogol C, Marlowe F, Tracer D, Ziker J. 2006. Plush punishment across man societies. Scientific discipline. 312(5781):1767-70.

Lucca G, Pospisil J, and Sommerville JA. 2018. Fairness informs social conclusion making in infancy. PLoS I. 13(two):e0192848.

Meristo M, Strid K, and Surian L. 2016. Preverbal Infants' Ability to Encode the Upshot of Distributive Deportment. Infancy 21(3): 353-372.

Schmidt MF and Sommerville JA. 2011. Fairness expectations and altruistic sharing in 15-month-old human infants. PLoS One. 6(10):e23223.

Sommerville JA and Enright EA. 2018. The origins of infants' fairness concerns and links to prosocial beliefs. Curr Opin Psychol. 20:117-121

Surian Fifty, Ueno M, Itakura S, Meristo M. 2018. Do Infants Attribute Moral Traits? Xiv-Month-Olds' Expectations of Fairness Are Afflicted by Agents' Antisocial Deportment. Front Psychol. 9:1649.

Xu J, Saether L, Sommerville JA. 2016. Experience facilitates the emergence of sharing beliefs amid 7.5-month-erstwhile infants. Dev Psychol. 52(11):1732-1743

Ziv T and Sommerville JA. 2017. Developmental Differences in Infants' Fairness Expectations From six to 15 Months of Age. Child Dev. 88(6):1930-1951.

Prototype credits for "Babies wait fairness"

Epitome of two babies interacting past santypan/ istock

Images credited to Schmidt and Sommerville announced under creative commons license. The images come from the paper (Schmidt and Sommerville 2011) cited in the references section above.

The same creative commons license applies to images credited to Surian et al (2018) and Lucca et al (2018).

Images of rectangles attempting to climb brown hill reproduced from a screenshot of a video posted by Uzefovsky and colleagues (creative commons license). I have modified the images (with arrows, hearts, and text) to convey the action.

Content of "Babies await fairness" concluding modified 5/22/20

Source: https://parentingscience.com/babies-expect-fairness/

Post a Comment for "Babies expect fairness, and prefer people who behave with fairness"